Dorothy might have been more fascinated with lions and tigers and bears, but we’ve been making litmus paper since Precision began, and we think it’s just as fascinating. Like the Wizard of Oz, litmus paper is a classic, so grab some popcorn and sit tight because this is going to be a good one.

Somewhere Over the Rainbow, Lichens Grow

Image: Rocella tinctoria, Source: Norbert Nagel

Did you know that litmus is actually made of dyes extracted from lichens? A lichen (lī-kǝn) is an organism in which there is a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and an alga. There are about 15,000 different recognized species of lichens, and they are geographically distributed across the globe, often in habitats too harsh for other organisms and plants.

Lichens are not plants and are not to be confused with mosses. They don’t have roots, stems or leaves, but they do live in similar habitats, such as moist trees, rocks, and cliffs. Lichens contain colorful dyes that can be extracted and used in various fabrics, rugs, and of course, litmus.

Certain species of lichens, known as orchils, are used for making litmus, including the commonly used Rocella and Lecanora/Ochlerechia species. Orchils provide purple to red-violet dyes when treated with ammonia.

Lichens themselves are generally pretty dull to look at, and it’s not until they’re processed that the dyes become apparent. Pictured above is the lichen, Rocella tinctoria. Hard to believe that’s the source of the bright blue and red in litmus paper, isn’t it?

The lichens are collected, dried, and stored until they’re ready to be processed. Litmus production involves a slow aerobic fermentation of the lichen in aqueous ammonia with the addition of potash and lime. It occurs over a period of a couple of weeks, and the end result is litmus powder.

Now which way do we go?

The term litmus comes from an Old Norse word meaning “to dye or color.” Fitting, right? Although Precision started making litmus paper in 1932, data suggests that litmus paper was originally developed in the early 1800s by French chemist, J.L. Gay-Lussac. We’d love to claim fame of litmus development, but it was just a bit before our time.

Back in the day, when Precision Laboratories was started in Cincinnati, Ohio, litmus was cooked in a 55 gallon trash can set up on a couple of cinderblocks over a meker burner. It was cooked this way for at least 12 hours, then left to cool and settle.

The hot water extracts the dyes from the litmus, and the solids are allowed to settle. The so-called ‘sludge’ sinks to the bottom. The liquid is decanted from the pot and used to treat the paper for our litmus test strips.

We know it’s not pretty, but hey, it worked didn’t it?

I’ve a Feeling We’re Not in Cincinnati Anymore

Today, we’re a bit more advanced in our litmus cooking methods, but the basic concept is still the same. The process involves multiple extractions of litmus with boiling tap water. If we are making red or neutral litmus, hydrochloric acid is added to the extracted solution.

Everyone in the building knows when it’s cooking because the smell of litmus is pretty unpleasant, but since we know where litmus originates, this comes as no surprise. (In case you’re curious, litmus test papers have no smell.)

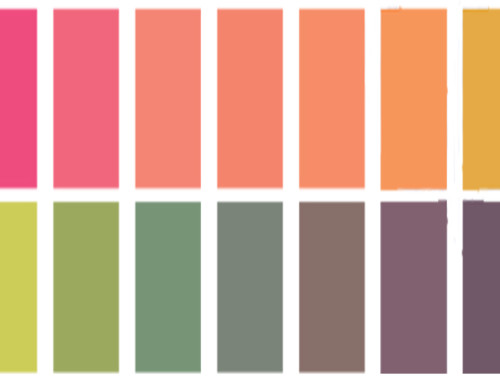

Once the papers have been treated with the extracted solution, they’re dried and cut. Depending upon the extracted solution used, the result is one of three different qualitative pH test papers:

- Blue litmus paper, which turns red under acidic conditions (pH < 7)

- Red litmus paper, which turns blue under alkaline conditions (pH>7)

- Neutral litmus paper, which turns red under acidic conditions and blue under alkaline conditions

Litmus test papers are qualitative because they don’t provide a defined pH value, and they don’t have a color scale. They change one color (with the exception of neutral litmus), so it’s a quick way to determine whether a solution is acidic or alkaline.

The actual pH range for Blue Litmus paper is 1-7, and the actual pH range for Red Litmus is 7-14. Neutral Litmus will work in either direction on the pH scale, but the best results are above a pH of 8 or below a pH of 6.

Litmus test papers have been around for ages, and they are continually used in classrooms today. While many people have used them, they may not always know the story behind litmus. We think it’s an interesting one to tell, and we’ll admit, we may have oversold it a bit in the beginning, what with the Wizard of Oz comparison and the popcorn and all, but we’re science geeks and it’s what we do!

Sources

“Lichen Dyes.” FAO. Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/docrep/v8879e/v8879e07.htm

“Litmus Paper.” How Products Are Made. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Litmus_Paper.aspx

Leave A Comment